[Maury Z. Levy: author’s note: In 1975, Muhammad Ali had been the king of the world for a long time. He was always surrounded by press people fighting for interviews. He talked a lot, but never let anyone get really close to him. Then a strange thing happened. He lost a fight to Joe Frazier. Reporters did a 180 and started following Frazier. Ali was alone. He wasn’t used to that. So, I got a call one morning from Ali’s press guy. He said Ali liked a Philadelphia magazine cover story I’d done on hockey flash Derek Sanderson. He said Ali wanted me to come up to his Deer Lake, PA training camp and spend a couple hours with him. The couple hours turned into a couple days. I got to train with him, I got unlimited access to him. Here’s the story…]

THE FORMER CASSIUS CLAY remembers when he was “just another nigger.” “It started back in Louisville. That’s where I was born. I was riding a bus one day. Didn’t have no Cadillacs yet. I was riding this bus and I was reading in this newspaper about Floyd Patterson and Ingemar Johansson. This was just when I had decided to turn professional, right after I won the Olympic gold medal in Rome. I was sure I could beat either one of them if I had the chance. But I was just as sure that I wouldn’t get the chance because nobody had ever heard of me. So I sat there thinking. How was I ever going to get a shot at the title? Well, it was right on that bus I decided. If I ever wanted to get noticed, I’d have to start talking it up. I’d have to do better than that. I’d have to start screaming and yelling and acting like some kind of a nut.

“You see, I figured if I did that, pretty soon people would get tired of hearing from me and they’d be insisting that I put my fists where my mouth was and fight whoever the champ was. They’d watch me fight. And I would float like a butterfly and sting like a bee. That saying has stuck with me to this day—float like a butterfly, sting like a bee.

“I started off pretty slow because I had to sort of feel my way around, find out what the folks, the reporters especially, wanted to hear. I told this one reporter I was going to knock this boy down in the sixth round, and he printed it and then I did it. That’s the first time I said I am the greatest. I figured if I didn’t say it, nobody else was going to say it for me.

“First the people were saying, ‘What’s that bigmouth talking about?’ But I kept fighting and talking and pretty soon people were saying I was the greatest. And I just said, ‘I told you so, didn’t I?’

“Now where do you think I’d be right now if I didn’t use all that shouting and hollering to get the public to notice me? Do you think I’d be sitting here in some $250,000 house in Cherry Hill? Hell, no. I’d be back down there in Louisville washing cars or running some elevator and saying ‘yes suh’ and ‘no suh’ and knowing my place. Instead of that, I’m the highest-paid athlete in the world and I’m the greatest fighter in the world. And that’s just the way I planned it.”

Like all things with Muhammad Ali, the former Cassius Clay, the explanation is a little oversimplified. But it’s very basically true. People around Philadelphia tend to take Ali for granted. Maybe it’s because he’s lived around here for the past five or six years, because he’s trained and done most of his talking around here. People just tend to see him as part of the local color. You lose perspective.

Well, Ali put it all into perspective right after another transplanted Philadelphian, Joe Frazier, had his heavyweight title beaten out of him a few weeks back. “I’m greater than boxing,” Ali said. “I am boxing. Muhammad Ali is the biggest thing in the history of all sports. I’m bigger than the Rose Bowl, the Super Bowl, the Kentucky Derby, all of them.”He wasn’t always this modest.

BACK IN 1960, before all his public pronouncements, before anybody ever really heard of him, he sat around a New York hotel with the rest of the U.S. Olympic team waiting to go to Rome. He was a promising light-heavyweight, having some casual conversation within earshot of a couple of writers. “I’m great, I’m beautiful. I’m going to Rome and I’m going to whip all those cats and then I’m coming back and turning pro and becoming the champion of the world.” His teammates just humored him.

In spite of what he said, he went to Rome a very scared 18-year-old, his only real confidence being in his feet and his fists, which he used to dance around foreign challengers and batter them with speed and grace and power. The then-Cassius Clay showed a sporting class that made him the talk of the games and the unofficial mayor of the Olympic Village.

Yet that was only one side of the man-child. It was the side that everybody wrote about and talked about. But it was only the surface. The greatest story never told was of Clay’s crush on Wilma Rudolph. Wilma Rudolph was a sprinter from the States. At that time she was the best in the world, garnering all that marked-down auxiliary publicity that goes with being on the women’s team. Clay was getting all the best ink. And Clay had this love-athirst-sight crush on Wilma Rudolph. But he was afraid to tell her. He was afraid even to make a move. She was, after all, the greatest woman athlete of her day. And Clay was just some humble young kid from Louisville who was good with his hands. He never even approached her. This was the real Cassius Clay. And 13 years after, it’s the real Muhammad Ali.

It’s the Muhammad Ali who almost let his wife talk him into leaving Cherry Hill and moving back to Chicago because she was homesick. The Ali everybody thinks they know just isn’t like this. Disregard the fact that Ali might be the greatest sports name of all time, that he’s made millions with his mouth, that he’s beaten the strongest of men. Forget all that. Ali is a Muslim. And in a Muslim house women are supposed to be subservient. How could Ali beat up all those mean men and then be bullied by a woman half his size? On the outside, Muhammad Ali has come a very long way from the Olympics. Inside he has gone nowhere.

IT’S A TWO-HOUR DRIVE from his home in the gardens of Cherry Hill to his new training camp in the woods of Deer Lake, a little bump in the road between Pottsville and Reading. Ali is building a whole training camp here that might even cost more than his house. It’s put together like a set of light Lincoln Logs. The big building has a boxing ring, some punching bags and a workout area. A mess hall is on its way up, along with some dormitory-type accommodations for his entourage.

Until that all gets up. they stay at a place on Route 61 called the Deer Lake Motel, where all the rooms smell from overdoses of Shell No-Pest Strips, and the business cards say “discreet lodging” under the name of the place. For excitement in Deer Lake, you go down to the local truck stop, open the broken screen door to the men’s room, put a quarter in the machine and get a little pack of naked women from 1950.

Ali doesn’t stay in the motel himself. He sleeps on the grounds of the camp in a $43,000 trailer with gold shag carpeting. He sits there and rests from roadwork, talks forever on the telephone and watches a strange parade of people come and go. Late at night, when most of them are gone, he sits around and talks about what was and what will be and what really is. He sits and does imitations of his life.

“I am the GREATEST! He’s going to fall in five! He falls in five. See, I backed up all that brashness. But like now I’ve changed as far as talking a lot. It’s just not the time. That was the style then—big mouth. That was my image. `I don’t talk jive, I’ll get you in five. I am the GREATEST! Let me get him! Don’t hold me back!’ Hell, that was all an act.

“I used to want to buy nothing but cars all the time. Cars and mink coats. Now I’m buying a farm.

“The world is a storehouse, you see, where all sorts of wines are collected.

“At that time I was boasting, I was drinking the wine of being flamboyant, of fame, of showing off. And now I’m out of that stage. I’m intoxicated with security. I’m intoxicated with doing something and ending up having something to show for all my time and my work. And so this isn’t the time for joking or talking. It’s not the time for playing.

“A man’s life is not that much different from the life of a child. A child takes a liking to a toy or a doll. Then the child gets tired of the doll. But at the moment the child took the liking to the doll, the child thought the doll was the most valuable thing in the world. But there comes a time when the child destroys the doll or throws away the toy. The same with man.

“Everything in America’s not real. It’s built on sports and entertainment. A train crashes in Chicago. It kills all those people. All that money. And they’re more worried about who’s going to win this basketball game.

“And since we’ve got a system that’s pleased to be puzzled, I puzzle them. I mystify them. See, a wise man can act a fool, but a fool cannot act a wise man.”

IN WISDOM, OF COURSE, there is strength. And only the strong survive. It is the strong will of Muhammad Ali that has outlasted everything. His punches might not be as strong as they used to, his footwork just a hair slower. But it’s surprising that the bumpy road he’s been on hasn’t taken more out of him.

Ali started boxing because he figured it was the quickest way for somebody who was black to make any kind of money in this country. He wasn’t very smart in school. He wasn’t even smart enough to be carried through to a basketball or football scholarship. It was just a lot easier to jump into the gym, learn the ropes and then turn professional. “If a fighter is good enough to be champ,” Ali says, “he can make more money in one fight than most ballplayers make in their careers.”

Ali was 12 years old when he first stepped into a gym. Six weeks later, he won his first amateur fight. By the time he was 13, he was fighting on television and gaining a pretty good following through his own advertising. When he knew he was going to be on TV, he’d run around knocking on all the doors in the neighborhood and tell everybody to tune in.

By the time he got to the Olympic trials in San Francisco’s Cow Palace, he’d had 180 amateur fights, winning most of them. He won those trials by beating the hell out of the champ of the U.S. Army, the organization that eventually knocked him out. Before the Olympics, he went back to finish school. He ended up number 367 out of 391 at Louisville’s Central High.

In Rome, he conquered Belgium, Russia, Australia and Poland. He returned to the States a hero, put himself up at New York’s Waldorf-Astoria eating five $8.50 steaks a day, and waited for things to start happening.

His first call came from a group of 11 wealthy white Louisville businessmen who offered to set up a syndicate to back their local hero’s professional career. In return for this, they would get half his profits and he would get a nice weekly salary and a tangerine-colored Cadillac.

His first pro fight was a win over a guy named Tunney Hunsaker, a tough white sheriff, and the first of a fairly long list of unknowns. “The important thing,” Ali says, “is that I was fighting and winning. I know I wasn’t fighting the greatest guys in the beginning. In fact, they were a bunch of bums. But every fighter does the same thing starting out. Liston did it, Frazier did it and Foreman did it.

“The only difference with me is every time I won a fight I made more enemies. Folks just didn’t like my mouthing off all the time. The more I kept mouthing’, the more folks would come out and root against me. They’d hope the other guy would bash my face in so I couldn’t talk no more and I couldn’t tell them how pretty I was. They’d yell things like, ‘Take away his pink Cadillac, the bum.’ Well, I don’t really care what people think about me or say about me as long as they buy a ticket to see me. Because that’s what it’s all about.

“I never really liked to fight that much, you see. It’s a hell of a way to make a living. But while I got to do it, I might as well make some good money out of it. Look, I’ve been boxing for almost twenty years now, since I was 12 years old, and I’m getting pretty tired of all this talking and all these people who want to do me in. But I don’t guess I’ll ever get tired of the money. It’s really the one thing that keeps me going.”

Early on, Ali was jumping at every chance to make a buck. He even cut a record. And this was way before Joe Frazier and the Knockouts. On one side of the record was a pretty tolerable version of an old Ben E. King song. But the other side was the one that sold. It was one of the famous Ali poems set to music:

This is the legend of Cassius Clay

The most beautiful fighter in the world today

He talks a great deal and brags indeed

Of a muscular punch that’s incredibly speedy The fistic world was dull and weary

With a champ like Liston, things had to be dreary Then someone with color, someone with dash Brought fight fans a-runnin’ with cash

This brash young boxer is something to see

And the heavyweight championship is his destiny.

OBVIOUSLY, HIS POETRY wasn’t going to win him any championships. And neither was his mouth. Certainly they would help him, but when it got down to the real natty gritty, when he got into the ring with another man who was out to bust his pretty little head in, there was just no way he was going to talk him down to the canvas.

Behind the mouth is a fighter, one of the best who ever lived. It’s not easy to describe Ali’s style or technique. In fact, if you looked at it closely, removed from the man, it’s hard to figure how he won all he did. Jose Torres, former middleweight champion turned writer, comes up with an inside description of Ali the fighter.

“Ali is not a great fighter in the conventional sense that Sugar Ray Robinson, Willie Pep and Joe Louis were,” Torres says. “Each of these fighters knew every punch and every move and added some tricks to the book, that unwritten book whose teachings are passed on from gym to gym and are the nearest thing we have to our own culture.

“Ali doesn’t have the power Robinson had. Unlike Louis, Ali doesn’t use his punching for defense and he doesn’t move like Pep. Nevertheless, Ali is the superior fighter of his time. We have a man who does not have the physical greatness of the greatest men of other times, yet his fists remind us that Robinson, Louis and Pep used to get hit with many more punches in one fight than Ali received in 20 fights. The explanation is simple.

“Muhammad Ali is a genius. He has a power that great fighters never had. Don’t watch Ali’s gloves, arms or legs when he’s fighting. Watch his brains.”

It’s a part of his brain they never developed in school. It’s the part that defies all logic and wins. From the outside, Ali is a dumb fighter. If you wanted to teach your kid how to fight, you wouldn’t tell him to watch Muhammad Ali. The guy does everything wrong. Anybody who’s ever been in a good schoolyard fight can tell you that.

He pulls away from a punch. You’re not supposed to do that. You roll with it, you duck it, but you don’t pull away. He carries his hands low. The first thing they tell you in a gym is get your hands up, protect your face, protect your body. You keep your hands down and you’re just inviting the other guy to clobber you, which is what Ali does. But just as the punch comes in, he pulls away like a cat, throwing his chin up in the air just to rub in the fact that you missed him.

He doesn’t penetrate you with his eyes. The best fighters will do that. They’ll stare you scared. You stand with Ali in the ring and his eyes look at you and look right past you. They’re glassy. They’re not so much the eyes of a man deep in thought. You don’t have time to do much thinking in the ring. They’re the eyes of a machine, a machine with a very precise movement, a machine whose body and feet work from the head, but whose hands work off of some sixth sense. Nobody’s mind could ever be as fast as that man’s hands. You can’t anticipate them. They move so quickly, you never see the punch. There’s no time for your eyes to send a message to your brain that you’re going to get hit and that you should move out of the way. It’s not so much the strength behind the punch that gets you, it’s the surprise that it came at all. And a quick punch you’re not prepared for will always hurt you more than a harder one you see coming and can roll with.

It was this kind of punch that got Sonny Liston in the second Liston-Ali fight. A lot of people watched that punch over and over again on instant replay and swore that Liston must have taken a dive, that a punch like that couldn’t have knocked him out, that it just wasn’t strong enough. Half of that is true.

Through the years, Ali’s fighting genius has allowed him to control his fight better than any other fighter of recent memory. He had such control that he could pretty much pick the round he would put his opponent away. This became a very big part of the Ali pre-fight circus. The press always pushed him for a poetic prediction. “He’ll fall in five. And that’s no jive.” And those predictions came through at a rate that had to beat coincidence.

With ten wins behind him, Ali moved into 1962 with some fights against people you might have heard of. He came to New York to knock out Sonny Banks and Billy Daniels, both in the predicted round. He went to Los Angeles to knock out an aged Archie Moore, also in the right round. He came back to New York in 1963 to miss his first prediction in a very brutal battle with a highly respected Doug Jones. Ali won a decision and gained the respect of a lot of people who didn’t like the circus. He went on to London to knock out British heavyweight champ Henry Cooper, as predicted. Now there was only one champ left, the heavyweight champion of the world, Sonny Liston. But first Liston had to take care of the only man standing in Ali’s way, Floyd Patterson.

IT’S BEEN ALMOST ten years. Las Vegas, as it always is, was very hot in July of 1963. The weather was about the only thing that wouldn’t change in the next few months. Muhammad Ali was still Cassius Marcellus Clay. John Kennedy was still safely in the White House. And some 15,000 U.S. Army noncombatant “advisors” were in Vietnam.

Ali, still pretty fresh from his slaughter of Henry Cooper, manages to get as much ink out of the Liston-Patterson match as either of the participants. He invades a casino where Liston is playing blackjack and calls him an ugly bear and challenges him to fight it out right there. He drives the old red and white bus into Liston’s camp with big signs all over it: Bear Hunting Season. Liston Will Fall in Eight. Big Ugly Bear.

Ali offers to fight the winner. It’s an offer that Sonny Liston can’t refuse. He makes duck soup of Patterson and goes into training to take on this brash 21-year-old kid, hopefully to shut him up for good.

Ali’s trainer and manager is Angelo Dundee, who’s been in his corner from the first fight. Dundee, an old and wise fight man, says he was in awe of Ali when he first saw him fight.

“There was always something special about him,” Dundee says, “something you couldn’t learn in books. He learned from people instead. Every place we went he picked up something else. He never forgets a fight, he never forgets a punch. The guy’s not just a great fighter, he’s an unbelievable human being.”

Dundee has been the main man in Ali’s corner. He was the one who tried to calm Ali down from all the hysterics and get him concentrating on boxing. Dundee was one of the few people who believed Ali could really beat Liston.

There were two other men always present in Ali’s corner in preparation for the Liston fight. One was Drew “Bundini” Brown, a well-traveled saloon-keeper who talked almost as much as Ali. Bundini’s title was assistant trainer, but he was really resident guru.

The third man you normally wouldn’t expect to see around a boxer. He was a lean black man with glasses and a very pensive look about him. He was an ex-hood, dope peddler and pimp who had worked his way up to become a chief spokesman for the new black consciousness in Harlem. He had been shown the light by the teachings of one Elijah Muhammad. His real name was Malcolm Little. On the streets of Harlem he was known as “Big Red.” To the rest of the world, he was Malcolm X.

THE LISTON-ALI FIGHT was set for February 25, 1964, in Miami. The weigh-in was the usual All circus. Ali was running around bragging, “I float like a butterfly and sting like a bee.” When Liston showed up, Ali begged Bundini to let him go, to let him fight right there. “You’re too ugly,” he yelled. “You’re not the champ, you’re the chump!” Ali got so worked up, the fight was almost called off. His normal pulse rate is 54 beats a minute. The fight physician clocked him at 120. “Clay is nervous and scared to death and he is burning a lot of energy,” the doctor said. The papers picked it right up and threw it into headlines: “Clay Scared.”

“Scared, hell,” Angelo Dundee protested. “With that kind of fear, I’d face a cage of lions. Liston was the scared one. He was so shook up he didn’t know what to make of the kid.”

The fight went on. There were people who thought the kid would be killed. After the first round, there was wild cheering at closed-circuit theaters all over the country. It wasn’t so much that Ali had won the round, it was just that he had made it through at all.

All kept dancing, moving, sliding in left hooks, sliding out of trouble. He was super-confident. He was cocky. The left kept coming. The right crossed over and hit Liston’s head. Liston began to become unglued. Like the big ugly bear Ali had called him, he rushed the kid heavily, trying to bully him down. Ali just danced away. By the middle of the third round Ali was in command. Liston could see the end coming. At the end of the seventh round, Liston sat down in his corner and didn’t come out again. He said he had hurt his shoulder and couldn’t continue. The truth was, according to his confidants, that Liston just plain gave up. He was an old and tired and beaten man. And the kid who had been yelling all these years that he was the greatest, finally was. Muhammad Ali, then Cassius Clay, was the heavyweight champion of the world.

After all the hoopla that went with it, Ali was driven from the arena to a black motel in Miami where he sat and ate vanilla ice cream from a dish and hammed it up for the tall man in the glasses who was taking pictures with a 35mm Japanese camera. The man was Malcolm X.

Around 8 o’clock the next morning, the two of them had breakfast together at the motel. They talked about Elijah Muhammad, the top Black Muslim leader. Malcolm said that Elijah and his god, Allah, had been rooting for Ali.

“Clay is the finest Negro athlete I have ever known,” Malcolm X said, “the man who will mean more to his people than any athlete before him. He is more than Jackie Robinson was, because Robinson is the white man’s hero. But Cassius is the black man’s hero. Do you know why? Because the white press wanted him to lose. They wanted him to lose because he is a Muslim. You notice nobody cares about the religion of other athletes. But their prejudice against Clay blinded them to his ability.”

It was the first real public mention of Ali’s Muslim leaning. The day became filled with a lot of questions from the press, almost none of them about the fight. Ali had said some pro-Muslim things in the few years that preceded, but this was the first time he publicly identified himself with the Muslims.

“I am not a black Muslim,” he said, “because that is a word made up by the white press. I am a black man who has adopted Islam. I want peace, and I do not find peace in an integrated world. I love to be black, and I love to be with my people. I am a very intelligent boxer, you know, and people don’t ask me about my muscles the way they would ask Liston or Patterson. They ask me about Zanzibar and Panama and Cuba, and I tell them what I think.”

All told reporters that Allah was in the ring with him against Sonny Liston, that he prayed to Allah five times a day, including once in his dressing room shower before the fight. He did, however, draw the line at subscribing to certain things associated with the Muslim movement. He said he did not hate the white man “because I would be nowhere today without the white man’s money.”

Ali had met Malcolm, who was not much of a fight fan, at a Detroit mosque a few years before. Ali was there with his younger brother Rudy, who was somewhat of a fighter but more of a Muslim. Malcolm had seen the Liston fight as a way to prove to the world the superiority of Islam over a white Christianity that had brainwashed the black community into accepting inferior status. Ali, fighting against another black man, had become the Great Black Hope.

Ali also announced to the press that day after the fight that he was giving up his “slave name.” From now on he would be known as Cassius X. The name didn’t last long, as Elijah Muhammad bestowed on him his new Islamic name. And Cassius X became Muhammad Ali.

THE EXTENT OF Ali’s tie-ins with the Muslims has been his best-kept secret. You ask him about the Muslims and he goes into one of his rehearsed lectures (he’s got 75 of them) . He starts throwing parables at you about wise men and fools. He says that Elijah Muhammad has come from God to teach us all a truth that has been hidden for 400 years. He says he is a Muslim minister. That’s when all his troubles with the draft started.

All of that is dogma. There is a very definite, if not sinister, relationship between Ali and Elijah Muhammad’s Muslims. There is good reason to believe that Elijah and his messengers have called the shots for Ali for the past ten years. There is certainly a financial tie-in.

Suddenly, Ali got a new manager. He is Herbert Muhammad, son of Elijah. And Herbert Muhammad’s cut of Ali’s purse is 50%. It’s strange, the Muslims never did dabble in sports. Elijah Muhammad doesn’t like them. But when Ali made the nine successful defenses of his heavyweight title, Elijah was right up there with him, in spirit anyway. Those fights paid a lot of money. But when Ali lost his title and his boxing license over his Muslim-supported avoidance of the draft, the love affair seemed to cool off.

Ali made most of his pocket money during that period from the lecture and talk show circuit while other people, certainly not the Muslims, tried to arrange for him to box again. Some three years later, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in his favor and Ali was given back his license, Elijah Muhammad suspended him, saying fighting wasn’t a fit thing for a Muslim to do. To this day, he’s still technically “suspended.” But his relationship with Elijah is still good.

This is the same Elijah Muhammad who suspended Malcolm X after his infamous “chickens come home to roost” comment on John Kennedy’s assassination. Malcolm then started his own faction of the Muslims and Ali turned his back on Malcolm and stuck with Elijah Muhammad. To this day, the whole situation is very embarrassing to Ali, who quite probably didn’t have much of a choice when it came to the Elijah-Malcolm split. Malcolm X, of course, was killed shortly thereafter in a seeming assassination by members of the rival Muslim sect.

Through it all, even his own suspension, Muhammad Ali remained spiritually and financially faithful to Elijah Muhammad. There is no telling why and Ali won’t say. People who know Ali well say he has always been easily manipulated. But no one is quite sure how deeply he’s into this whole thing. At least no one is willing to talk about the Muslim’s hold on him.

Other top black athletes have been lured by the Muslims since Ali. One of them is Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, the former Lew Alcindor, the basketball player. Recently, a house he owns in Washington was the scene of seven slaughters in what seemed like another Muslim factional dispute. A witness to the massacre said one of the killers fleeing the scene yelled back, “Don’t mess with Elijah.”

There are people around who still insist that poor Sonny Liston was intimidated by the Black Muslims into dumping two fights to Ali. Meanwhile, Ali is playing the whole thing as coolly as he can. And evidently he is playing it right, because he is still alive and well and living in Cherry Hill.

ALI’S BEEN LIVING in the area for most of his exile, right on through his return to the ring. The man most responsible for bringing him here is Major Benjamin Coxson, who is the furthest thing you could find from a Black Muslim. Coxson is a colorful local black businessman. No one is quite sure just what business it is he’s in, but he’s doing very well at it, when he isn’t in trouble with the law. Coxson is now in the process of running for mayor of Camden, something he considers a necessary step on the road to the governorship. Coxson says he is running on his record. “Most politicians end up in jail anyway,” he says, “so I’ve got a head start.”

Coxson met Ali somewhere around 1968, when Ali couldn’t get a fight. “I wanted to see if I could take on the challenge of getting him a fight,” the Major says. “I called every governor in the country. I got a lot of bullshit. I figured I’d go down south. At least I’d get a straight answer. I contacted John Williams, the governor of Mississippi. He had one arm. He didn’t know if I was black or white. I went down there with Gene Kilroy. Gene is white. He was selling telephones in briefcases. He sold one to me and I later got him a job with Ali.

“Well, we went down to Mississippi and we got into the governor’s office because they thought Gene was me. Anyway, we set up a fight and came back to Philadelphia and called a press conference at the Bellevue to announce it. But the U.S. government stepped in and said if Mississippi let the fight go on, they’d withdraw all their funds. So that killed that.” It didn’t quite happen that way, but the Major has always been good at embellishing stories.

Coxson met Ali driving one of his fleet of fancy cars down 52nd Street when Coxson was still living in Philadelphia. There was a lot of hell being raised by the Black Coalition, led by Jeremiah X, a minister and former classmate of Coxson’s at Ben Franklin High. Ali saw Coxson’s car and told him he admired it. Coxson invited him out to his house at 72nd and City Avenue to see the rest of the collection.

“I had the proper things,” Coxson says. “You just can’t overlook them. We saw more of each other. We’ve become closer than friends. We’re like brothers now.”

It wasn’t only Coxson’s cars that Ali admired. He ended up buying his house. It’s not every house that has carpets and chandeliers in the garage. Coxson, who had demonstrated his dexterity with money matters, became somewhat of an advisor for Ali.

“When he was getting ready to fight Frazier,” the Major says, “I saw where the City of Philadelphia was going to take 90-some thousand dollars in city wage tax off his purse because he lived in Philadelphia. So I saw a way to move him to New Jersey to beat the City out of their money.

“I was just finishing up a house in Cherry Hill and it was perfect for him. He’s such an unbelievable man. I should be Muhammad Ali for a week. There’s nothing he couldn’t do or nothing he couldn’t be if he made his mind up about it. And he’s such a good-natured guy, you’ve got to watch out for him. A lot of people will show him things and think he’ll go along.”

Is he that easily manipulated?

“No,” Coxson says. “I said he was good-natured. I didn’t say he was an idiot.”

THE COXSON-ALI fondness is mutual. Ali kiddingly refers to Coxson as “the gangster.” At least I think he’s kidding. “The Major made me move to Philadelphia,” Ali says. “At least his house did. I bought the place with money I made from college lectures and TV appearances. And I was really getting set never to fight again. So this was a nice home, nice neighborhood, prosperous-looking, to reside in forever.

“Philadelphia was a good town. I wanted to get out of Chicago because I was in New York twice a week and I found myself living in airplanes, which I hate. New York was too busy. And Newark and Trenton, I looked in those places but there was nothing I liked. So I stayed with Philly.

“But after I started to fight again, the house got small. We had another child or two. So then the Major showed me another house, this big, beautiful Spanish hacienda. I went and looked at it and didn’t like it because I figured it was too far from Philly. I like to live around people and everything. But I got to start hanging around with the Major a lot over there—he lives down the block—and I got to like the peace and serenity of it, being away from the people.

“The house needed a lot of work done to it, so I put another $150,000 into it. Plus I paid $115,000. And I made a little mansion out of it. I’ve got a lot of land. There’s an acre-and‑a-half around it. And now I’ve got that house up for sale.

“We’re working on another deal. Still around Cherry Hill. A 65-acre farm with a house on it, horses, barns and everything. My wife Belinda likes horses and I’d like to have a couple of milk cows. A little garden for myself, maybe. Probably grow cabbage, corn, string beans, tomatoes. Just a hobby like. Maybe the Major’ll teach me how to grow money.

“The Major’s some man, I tell you. I get on Johnny Carson and talk about him. I tell Howard Cosell about him after my fights. My telephone! Gene, where’s my telephone? Let me show you something else the Major got me for nothing.”

Gene Kilroy brings over one of his briefcase telephones. Ali opens it up like a kid unwrapping a Christmas present. He starts pushing some buttons and yelling, “Mobile operator! Mobile operator!”

“You can be in your car or just walking around and you can talk to anybody in the world. Major Coxson. I run into him, he had one, he got me one. He’s somethin’.”

ALI HAS TURNED OUT TO be a pretty good transplanted Philadelphian. At least he’s tried to get involved in some local things. When there were serious racial problems in South Philadelphia’s Tasker Homes a couple years back, Ali went down there with the Major and Stanley Branche to try to calm things down. He thought that as a hero to the young, he could talk some sense into them. It was the first real knockout of Ali.

The kids saw him come down there in a fancy car. They figured he must have been doing the whole thing for the publicity. They got very mad about it. There were a lot of bad words thrown at Muhammad Ali. The last were, “Get out of here, you white nigger.”

All left. He was very hurt. He was, after all, the champion of the people. And these were the people. Ali was not out for publicity. Inside, he is really too shy to know how to play that publicity right. He continues doing things around Philadelphia, things you never hear of because Ali doesn’t call press conferences and go shooting his mouth off about them.

He’ll spend hours in a Shriners’ hospital talking with the kids in the wards. One day he got into training camp late because he heard a thing on the news about this little kid who had gotten his legs cut off by a train. He went to the hospital, unannounced, and held the kid in his arms and started dancing around. “This,” he said, “is the Ali shuffle. And one day you’re gonna be doing it yourself.”

The three-year layoff gave Ali a lot of time for this sort of thing. He had scored in the 16th percentile in his pre-induction written test for the Army. He says the questions were too tough.

“A vendor was selling apples for $10 a basket. How much would you pay for a dozen baskets if one-third of the apples have been removed from the basket?” “(a)$10 (b)$30 (c)$40 (d)$80”

“I didn’t learn none of that stuff in school,” Ali says. “I was a fighter, not a mathematician. I just looked at those questions and I didn’t even know where to start.”

The Army decided to give him a break. A month later they called him back for another test. The results were the same. So when Muhammad wouldn’t come to the Army, the Army went to Muhammad. They lowered their standards. All of a sudden, the 16th percentile was made the passing grade.

Ali refused to go, citing his newfound status as a Muslim preacher and the Islamic teachings against war. “Anyway,” he said, “I ain’t got no quarrels with the Viet Congs.”

His draft resistance cost him his title and his right to fight. He had taken the hard way out. There was no way Muhammad Ali would have ever seen combat. The Army would have done with him what they did with another heavyweight champ, Joe Louis. They would have hired a special plane to take him around to different bases to put on exhibitions for the guys. They’d ask him to tell a few stories, throw a few punches and leave. He would have been a black Bob Hope. It became a matter of principles. Ali kept his principles but lost the fight.

IN THE YEARS of the layoff, the bottom almost fell out. There’s a story around about a plumber who had done a job at Ali’s house in Philadelphia. One day the plumber came knocking at the door holding Ali’s check in his fist. The check had bounced. “I’m sorry,” Ali told him, “that’s the way it is. I have no money.”

Whatever money he did have over those years was drawn from personal appearances. “I spent a lot of time on the Johnny Carson show,” he says. “I hated every minute of it. What a bunch of bullshit. All that kissin’ and laughin’. All them actresses with the funny accents talkin’ about their poodles.”

All even tried his mouth at the Broadway stage. He starred in a play called Big Time Buck White. It lasted seven performances before closing.

And then finally, in 1970, just when everybody was counting him out, he won his case against the Army. His boxing license was restored. There was immediately talk of the fight of the century, an undefeated Ali against the then-undefeated champ Joe Frazier. Frazier was in no hurry for such a fight. But Ali hounded him.

Both Ali and Frazier were doing their training in Philadelphia. And both were doing some running in Fairmount Park. One day they almost ran into each other. Ali threw up his fists and started making like he wanted to fight it out right there.

“You really think you can whup me?” Ali asked.

“I’ll whup Mamma if she try to take my title,” Frazier said.

“I think you mean that, Frazier.” “You doggone right I do.”

“Well, let’s get it on right here.” Ali put up his fists and started flicking his left. Frazier got unnerved. That’s just what Ali wanted.

“Not here,” Frazier said, “not in private. You show up at the PAL gym and we’ll see who the real champ is.”

Ali showed up. So did 1,000 fans and the police. The police suggested they take it outside, back to Fairmount Park. By now the crowd had doubled. Ali had a pretty good audience.

“He wants to show he can whup me,” Ali shouted. “He says he’s the champ. Let him prove it here in the ghetto where the colored folks can see it.”

Frazier never showed. Ali seemed very mad.

“Here I am,” he yelled. “I haven’t had a fight in three years, I’m 25 pounds overweight, and Joe Frazier won’t show up. What kind of a champ can he be?”

In the months that followed, Ali would find that out. But first he had a couple of warmups to fight against some pretty fair fighters, Jerry Quarry and Oscar Bonavena. Quarry went easily. Bonavena lasted 15 rounds. It was a good test for Ali. Many people were amazed that after a three-year layoff he could come back that strongly. The really amazing thing, though, is that he came back at all.

His fights became spectacles again, full of stars and cars and fancy clothes. The champ was back and so were all of the Beautiful People. Everything was like it was before. Now all he had to do was beat Joe Frazier.

Cus D’Amato, a legendary fight manager who’s been seen around the Ali camp more and more since the comeback, summed it all up. “Boxing,” he said, “isn’t a sport of skill. It’s a sport of will. Joe Frazier can punch good. He can come hard. But he’s dumb. He’s got the skill, but not the will. Eventually he’s just going to give up. Ali’s got skill and will, but mostly will. It’s just a matter of who wants to win the most and that’s Ali. I’m telling you, there’s going to come a time when Frazier’s just going to give it up.”

D’Amato was prophetic, only not for this fight. The Ali-Frazier fight was the biggest money match in history, each fighter guaranteed $2.5 million. It was a meeting of undefeated champions. It would answer the question everyone had been asking for years: Did Ali still have it in him?

The answer was yes. Except on that night in Madison Square Garden, he didn’t have quite enough. A more conditioned Frazier wore him down. By the late rounds, Ali’s legs started to give out. He was just plain tired. And that’s where he lost the fight, in those late rounds. On most people’s scorecards it was a very close fight. There are those who say that Ali won. Unfortunately, none of them were judges for the fight.

Frazier, still the champ, went into the hospital right after the fight. He won but he had paid for it. No one was saying just what was wrong with Frazier. There was some talk of a blood circulation problem caused by Ali’s punches. Was Frazier really all right? The answer wasn’t to come until almost two years later.

MEANWHILE, Ali went back to camp, having to face still another comeback. This time things were a little different. Somehow the beautiful people were gone. And all those stories about Ali that kept popping up just about stopped. He was over 30 and, some people thought, over the hill. Right before the Frazier fight, there had been 600 newsmen hounding Ali for interviews. Now, in the deserted pines of his Deer Lake training camp, Ali was alone. He missed the people and he missed the publicity. The idea to start this story came from Ali’s camp. It was the first time, as far as anybody knows, that Muhammad Ali had to ask for a story to be written about him.

The phone call came from Gene Kilroy, the Major’s old friend. “Listen,” Kilroy said, “Muhammad was just looking at this story you did on this hockey player who’s making all that money. You put that guy on the cover. Muhammad wants to be on the cover too. Hell, he makes more in one fight than that guy’ll make in ten years. Come on up, Muhammad wants to see you.”

Ali was happy to see anybody. We sat in his trailer and talked a lot. He did most of the talking. It was getting very late and I started to leave to go back to the motel. I told him we’d have plenty of time to talk the next day. I was afraid of wearing out my welcome. “Stay where you are,” Ali said. “I’ve got no place to go.”

We sat in the trailer and watched a videotape of the Frazier fight. Ali must have seen it a dozen times. It’s almost like he’s hoping the ending will turn out differently. He moves with the punches. He yells encouragement to himself, as if the little man on the screen were somebody else. We watch all 15 rounds. There is a lot of hollering, a lot of second-guessing. And at the end they announce the winner. It is still Joe Frazier.

All the while, Rahaman Ali, the former Rudy Clay, the kid brother, is sitting at the kitchen table eating bean soup. I have quickly grown to dislike Rudy. It all started when I was introduced to him. I extended my hand. Rudy just stared at it and then looked up at me and said, “I’m sorry, I’m eating. It’s unsanitary to shake hands while you’re eating.”

Rudy is the red-hot Muslim. He got into it more quickly and more deeply than his brother and, some people suspect, probably pulled Muhammad down with him. Rudy is much more militant, though. For one thing, he hates white people.

Rudy keeps coming on strong. Muhammad tries to shut him up. Finally he just pulls me outside. “You’ve got to come look at my new bus,” Ali says, taking me around back to see his latest toy. “Just look at this,” he beams, “it’s got toilets and a bedroom and everything. I even drive it sometimes. What do you think?”

“I think maybe I’ll give up writing and become heavyweight champ,” I tell him.

“My man,” he says, slapping me on the back, “you be the fighter and I be the writer.”

I’ve made a friend. We make plans to meet early the next day. “You know,” he says, “most of the guys who come up here to interview me, they don’t really want to hear what I have to say. They just want to have their picture taken with me or get in the ring and spar a little bit so they can tell their friends they fought the champ. But you don’t want to do that, do you?”

“No,” I say, lying.

“You’re all right,” he says, slapping me on the back again. “You’re not as dumb as you look.”

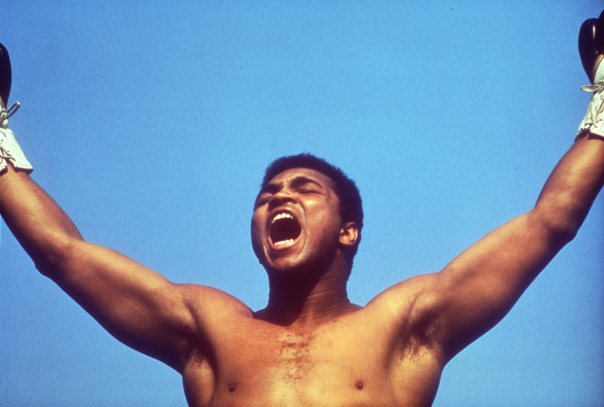

WE GO TO THE GYM the next morning to set up some pictures. Ali puts on his best pair of boxing trunks. His belly is hanging over the waistband a little. He knows he’s not in the best of shape. You can see it the most from the back. That once beautifully formed back is just so much jelly now.

Elizabeth Richter, who’s taking the pictures, asks him to climb into the ring. He climbs in and leans on the ropes. Gene Kilroy comes over to Elizabeth and whispers. “Try not to shoot from that angle,” he says, grabbing the fat around his own waist. “You’re getting too much of his roll.”

The formal pictures over, Ali starts his workout. He toys with the speed bag and then goes over to the heavy bag, making believe it’s Joe Frazier. Every punch has a sound. “FFFFTT. FFFFTT, FFFFTT, FFFFTT.” He pushes the sounds through his clenched teeth. The 100-pound bag is moving. The punches come long, from an 82-inch reach. And then he moves in for some close work, keeping his hands in on his 42-inch chest, his head bobbing around his 17-inch neck. At 6’3″, he’s almost punching down.

When he’s finished on the bag, he picks up a jump rope and starts skipping in front of a large mirror. On one side of the mirror is a blowup of him when he was 12 years old, a lanky kid in boxing gloves. On the other side is a cardboard poster announcing the Frazier fight that is now history. Ali stares straight into the mirror. Even with the added weight, even with the flabbing of some muscles, the loss of a little speed, he is still a handsome specimen of a man. He really hasn’t lost that much. But in boxing, just a little bit is often too much.

All moves to the ring with the red, white and blue ropes. He spars a few rounds with three different guys. Ray Anderson is a defector from Frazier’s camp. He knows Frazier better than anybody. Eddie “Bossman” Jones is shorter and stockier, built more like Frazier. Ali just does a little dancing around with the two of them. Throwing very few punches. Ali doesn’t like to punch when he’s sparring. He likes to be punched. That was his problem against Frazier. He didn’t have much trouble landing punches. He never does. But he got worn down by the punches he took. If he’s going to come back, he’s got to get used to the punishment.

The last man in with him is Billy Daniels. Billy Daniels was once a promising heavyweight. On the night of May 19th, 1962, Muhammad Ali knocked him cold. Daniels was never the same. He is here at camp because he needs a payday. Ali will give him $1,000 for two weeks work. Daniels is a pathetic sight in the ring. He can hardly get his punches off. Ali tries to make him look good. He drops his hands and invites Daniels to lay one on him. Daniels comes through with a shot that couldn’t have rung a bell. Ali goes into one of his better acts, making like the punch dazed him and dropping to the canvas for the count. He gets up laughing.

“Ain’t nobody gonna hurt me,” he says, “I’m too pretty.”

The workout is over. He showers and goes back to the trailer to rest. He leans back and sips some freshly squeezed juice.

“See,” he says, “you gotta be black to appreciate just how pretty I am. The people all know that. Look at my skin. Look at how nice and bronze it is. Not Frazier. Frazier is real dark, real black. He’s just an ugly nigger. His face is all cut up. Me, I’m too pretty. I never been cut, ever.”

ALICOULDN’T SAY that for long. Two weeks later he was in Stateline, Nevada, knocking the hell out of light-heavyweight champ Bob Foster. Ali commanded the fight. It seemed like he could have easily put Foster away early, but he toyed with him. Foster was on an elevator, up and down through the whole fight. Ali waited until the eighth round to put him away. The fight was costly, if nothing else, to Ali’s pride. He got cut. He came out of it with a two-inch slice at the corner of his left eye.

“He got that cut because he played around too much,” Bundini Brown said. “He just can’t play around with important things. The man has got to stop that.”

Why did Ali play around so much? Why did he carry Foster so long? The answer might have come two weeks before in the trailer at Deer Lake.

“Now I’m gonna fight Bobby Foster,” he said. “He must fall in eight! I’m predicting. He’s goin’ in eight! People like that. You’d be surprised at the excitement and drama. Now I’ll try to do it. If I don’t do it, I don’t. But I’m gonna try. But, see, that’s not me. I got over that. But you got to please a lot of people because that’s what they pay to see.

“Gorgeous George was a wrassler. He entertained them. ‘I’m pretty.’ He knew what they wanted. ‘I can’t lose.’ And he got everybody going his way. Now who’s the fool? Them. He’s the wise one. He’s leading the whole world. He knows just what to take, just what to give.

“And I know what I’m doing. I have a goal. And I’m determined. I’ve drunk the wine of success. The government can take away my title. And they did. Jail was right on me. The money was gone. I couldn’t fight no real fights. No commissions. Couldn’t box exhibitions. I still didn’t give up, man. I’ve been too successful.

“From 12 years old, I’ve been the U.S. Golden Gloves champ twice, world AAU champ, Olympic champ, Pan American. I don’t know failure. And they said, ‘You can’t fight.’ And I said I’m not worried about it. And Ijust kept going. I knew something was gonna happen. Wise men know all. And that’s me.

“Did you know the wisest men in history were illiterates? Men like Jesus, Moses, Lot and Noah. They were illiterates. Now why did God come to Moses, who couldn’t read or write? Why did God come to Moses, who couldn’t even talk? Aaron had to talk for him. Check history.

“Who is Elijah Muhammad? How is he converting whores and faggots and sissies? Buying airplanes and factories and uniting black people. Teaching them the language, the culture. Who is Elijah Muhammad? He’s never been to school.

“See, who is Muhammad Ali? I barely got out of school in Louisville. It’s on the record that they put me out because I was gonna •be the Olympic champion. I can’t read and write now.

“Then where is this stuff coming from that I challenge anybody to match with his wisdom? It didn’t come from no libraries. It didn’t come from no schools.

“Now people say I done a lot of things besides boxing. Stood up to the draft and all. Helped kids in hospitals. I don’t boast about that. Wise men never boast. You never forget where you came from. The house I was raised in cost $4,000. I got a motor scooter that took me all through school, all through my amateur career. That motor scooter cost $35 and we never had enough money to pay for it.

“I never bought mink coats or drove around in limousines with chauffeurs because I remember who I was. I remember my people. I only have one suit now. I can afford to buy the store. But the greatest men in history were humble.

“If Jesus came to town tonight, he wouldn’t be staying at the Waldorf-Astoria hotel. He’d be up in Harlem somewhere trying to get somebody off drugs. Wise men are humble. They don’t boast. Elijah Muhammad told me that. Never forget where you came from.”

MUHAMMAD ALI has never forgotten where he came from. Now he’s trying to figure out where he’s going. Up until a few weeks ago that wasn’t so hard to figure out. He was going to fight Joe Frazier for the title again and earn a $3 million guarantee. That was until Joe Frazier blew it.

Looking like the Goodyear blimp, Frazier went to Jamaica to defend his title against another former Olympic champion, George Foreman. Not since Ali’s second knockout of Sonny Liston has a top heavyweight looked so bad. Foreman all but killed him. Frazier was down six times in four-and-a-half minutes and they stopped the fight. Foreman was the new champ.

Ali didn’t go to the fight. He stayed in Deer Lake and sent Angelo Dundee with instructions: “Make sure nothin’ happens to Frazier.” Dundee was noticeably nervous before the fight. “Frazier loses and there’s no fight with Ali,” he said. “He’s throwing away millions. Believe me, the kid Foreman can punch. What’s Frazier trying to prove?”

Joe Frazier proved that even though he had beaten Ali, he couldn’t come back from the beating he suffered. Frazier looked finished. Back in Deer Lake, All was livid.

“Frazier was dumb, dumb, dumb,” he said. “Frazier is washed up. If he’d been smart, he’d have fought me again first to get the big money. But he didn’t want no parts of me after what I did to him in the first fight.

“George Foreman should pay me because I’m the one that beat Frazier down. He’s been hurt ever since. That’s why he’s been fighting nobodies. Foreman was the first decent fighter he fought and Foreman beat him.”

What happens next? Well, you can bet George Foreman will duck Muhammad Ali as long as he can. Foreman is a flat-footed puncher. And Ali is a more classic boxer. On percentage, a boxer will always beat a puncher. But all Foreman has to do is stall. Ali gets older every day.

IT’S JUST ANOTHER MORNING in Deer Lake. The orange sun crawls up over the hills and burns off the deep purple haze. Down the dirt roads that surround Pollack’s Mink Farm, Ali is running alone. Three miles with the wind in his face. He is trying to keep in shape. For what, now he is not quite sure. But he is running. He doesn’t talk. He shows no emotion, no fatigue. He is a machine. He finishes his three miles and stops next to a big rock in the grass and takes a few swings at his shadow. He stops and lifts up the waistband of his plastic sweatshirt. Four pounds of water fall out and splash the ground. He sits down on the rock to rest.

“I don’t need no world championship,” he says. “Everybody knows I’m the number one attraction in the world. I’m the champion of the people. You go into the ghettos and ask them who the champ is. You go anyplace in the world and ask them who the champ is. They’ll tell you Muhammad Ali. It don’t matter what happens anymore. I’m still the champ.”

He sat there alone on the rock. There was nobody there to hear him. He walked up to the highway, Route 61, where the cars were going by at 60 miles an hour. “You hear that,” he shouted, “I am the champ! I am the greatest!” Nobody even slowed down. His face got mean. “Can’t you fools hear me?” he yelled.

this is in my opinion one of the best article i have ever read about Clay/ Ali. Bravo Levy

The most captivating story about Ali that I have ever read. Information never before written about!

[…] Poor Butterfly: The Muhammad Ali Story In 1973, Ali had been the king of the world for a long time. He was always surrounded by press […]

[…] Medal, his interview with Levy has resurfaced as Levy goes through his own archives. You can read the story he wrote for Philly Mag on Levy’s blog over here, or listen to audio of his talk with Ali here. Both are worth your time. This entry was posted on […]