By Maury Z. Levy

Saturday is pink, which is only fitting. She is standing there in the middle of the newsroom, Jessica Savitch, somewhere in between Orien Reid and Al Meltzer, and she is flashing her panties.

Maybe this is not the most professional thing to do. Mort Crim doesn’t go around showing his jockey shorts in public. But then Jessica Savitch is still pretty young, 26, and pretty green—they fix that up with makeup.

The panties are a gift from an admirer in Allentown. There are a lot of them, admirers. There is even a whole Jessica Savitch fan club, people who do nothing but live for weekends at 6:00 and 11:00 on Channel 3 to watch her anchor the local news, people who sit there all week through four newscasts a day hoping to catch a glimpse of her reporting on a fire.

It has become a cult, almost. Jessica Savitch, in about a year and a half here, has probably gained the biggest following of any local female television person since Pixanne left. She did leave, didn’t she? Or maybe she’s doing Gene London’s show.

Anyway, she is holding up the panties, the different-colored ones that came in the plain brown wrapper, she is holding them up, all seven pair of them, and reading off the days of the week embroidered on them, which she already knew by heart. Don’t let that blonde hair fool you.

There is a card, a big one, that came with the gift. The guy from Allentown paid two and a half bucks for it. It’s your basic Hallmark foldout, but he’s written his own messages on it in pencil: “How would you like to spend a weekend at a ski resort with me? I love you much. I am very interested in marrying you.”

The panties were nothing new. They send her gifts all the time, these people. One Christmas, some guy sent her five $100 bills and didn’t bother to sign the card. “I’ve enjoyed you all year,” he wrote, “and I just wanted to thank you. Please buy something nice for yourself.” Jessica Savitch gave the money to charity.

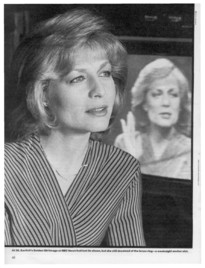

She says she doesn’t understand a lot of this, how she has become the sex symbol of the ’70s to a lot of people in Cherry Hill and Chestnut Hill and at least one guy from Allentown. She appreciates it and she resents it. Jessica Savitch, who has a very pretty face, is not just another pretty face. In fact, she’d even give you an argument on the pretty part.

“I’m a very flawed person,” she says. “I’ve got this lisp. People in television are not supposed to have a lisp. I have a very square jaw and my skin breaks out terribly and my hair just never lies flat and my front tooth is chipped.” She forgot to mention that her legs are skinny, which is why she never wears dresses.

But somehow the way it all falls together is enough to knock you over.

She didn’t always look this good. She used to purposely tone down her act, because if she came on too much like the blonde bombshell, people would only talk. They’d say she got her job by flicking her eyelashes or dating the program director. The raps are nothing new. She’s got a lot of things going against anybody recognizing the real talents she has—the brains, the imagination, the drive, the on-camera presence in a medium that has been dominated by men.

“I had no one to emulate,” she says. “Who did I have to try to be like? Walter Cronkite? John Facenda? Read the rest of this entry »