[Author’s note: My first job in media, when I was still in college, was as producer of Jack McKinney’s top-rated talk show on WCAU radio. We played a lot of Clancy Brothers’ songs.]

[Author’s note: My first job in media, when I was still in college, was as producer of Jack McKinney’s top-rated talk show on WCAU radio. We played a lot of Clancy Brothers’ songs.]

BELFAST, BRITISH OCCUPIED NORTHERN IRELAND—Mist over the hills missed over the city, which is the color of oatmeal now. Cold, though. Eats your bones, makes you sick. No heat, just coal. The lesson of two evils. A child is dying of black lung. An old woman has already gone. Sean is in the basement mixing up some medicine. Johnny’s on the pavement thinking about the government.

Eamonn McCann, who is the real Bernadette Devlin, is watching Jimmy the Dummy on the telly. The Royal College of Physicians has just come out with a report that says cigarette smoking is hazardous to your health. Cigarettes. They are telling the viewers who are out every night in the streets getting pieces of their bodies blown off by petrol bombs that cigarette smoking could give them cancer in the long run.

On the tube Jimmy the Dummy sits on the ventriloquist’s knee smoking and choking, the dumb little twirp. Eamonn McCann is rolling on the bed under the posters of Martin Luther King, Nikolai Lenin and Karl Marx, none of whom have cracked a smile. Jack McKinney (enter the hero) is sitting by the phone gagging on a guzzle of whiskey.

Jimmy the Dummy is the BBC’s way of reaching the young. He is worked by an older man who never moves his mouth, only his eyebrows. There is no way they can crop the guy’s eyebrows out of the picture so they move in and hold on a tight shot of the dummy. “Stop now before it’s too late,” the dummy tells the young people.

EAMONN MCCANN is 27. A lot of people consider him the most articulate political voice in all of Ireland. He is head of the Derry Labor Party. But most of the time he is prince consort to Queen Bernadette. He is a burning bush of hair, the wiseman from the North. So here is the best Christ symbol Ireland’s got sitting on the iron bed in Jack McKinney’s flat watching Jimmy the Dummy and waiting for the devil.

This was to be a summit of sorts among three of the major forces in the Irish revolution: Devlin, McCann and McKinney. Queen Bernadette, as is her custom, was late.

“I guess I’d better call and see that she hasn’t gotten her bloody little head blown off,” McCann says. He rings her up at her home in Cookstown, County Tyrone. “She’s what? Taken a taxi? It’s almost 60 miles from there to Belfast. Oh well.” He hangs up. “She’s gone and done it now, Jack. Somebody’s going to find out about this. Miss Devlin, M.P., symbol of the struggling masses, is taking a 60-mile taxi ride.”

McKinney is too busy watching Jimmy the Dummy choke to death. “Yeah,” he says, “she probably won’t be coming here then. She’ll probably go right to the cocktail party. Come on, I may as well drive you over now.”

“No, wait,” says McCann, “cocktails at the Irish Times can hold. I want to wait and hear the news. . . .”

“And in Northern Ireland, British troops are investigating the terrorist explosion that blew up a BBC transmitter last night, disrupting service to most of Ulster. For a film report, we switch to . . . .”

“How about that,” McKinney says. “Look’s like we’re in for a little action again.”

Eamonn McCann does not say a word. There is a coy, knowing smile on his face as he watches a British soldier walking toward the camera with a large charge of unexploded jelly.

“Okay, Jack,” McCann says, “we can go now.”

THERE IS NO TROUBLE in Belfast that night, maybe because all of the leaders are at the cocktail party given by the Irish Times. Never let a revolution get in the way of free drinks. If the. British troops really want to end this thing they should shoot Bushmill, not bullets. At the cocktail party, few talk of the jellybomb. Only Frank Gogarty, leader of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) , is doing any real talking.

“Things have been too quiet lately,” he says. “Maybe we’ll be seeing a little more action now.”

Queen Bernadette, who has finally arrived, and Prince Eamonn are listening closely to what Frank Gogarty says. They know it is not idle speculation. Frank Gogarty is a father figure. There are few of them left. He is a dentist by profession, a thinning, grayish, tired man with a wife and six sons. He is appealing one six-month jail sentence for conspiracy and waiting trial on another. Frank Gogarty has a piece missing from his left ear, pierced by a British bullet. Men with pieces of their ear missing do not make idle speculation.

The next night, the forces of the devil tar and feather two men near Ballymurphy, an already ripped “no go” section of Belfast. “No go” means that the cops and the soldiers have pulled out of this religiously split area. They have withdrawn to a policy of containment, your basic letthe-bastards-kill-themselves-off-as-long-as-they-keep-it-in-the-neighborhood approach. Because of this, volunteer vigilantes are left to patrol the area and maintain their own brand of law. The Catholic vigilantes made two arrests that night, one on a trumped-up drug charge, the other for “interfering with our Irish women.” The quick tarring and feathering of the two Protestant prisoners touched off a week of rioting, most of it at night, with the streets lighted by the fire of 100 petrol bombs.

On the first night of rioting, rack McKinney got in his battled gray Anglia and drove up to Ballymurphy for a first-hand look. The car had been acting up all week, the clutch was too chewy and the brakes wouldn’t bite. It chugged along the narrow lines of battle, up the hill to the main drag, where it finally stalled.

Jack McKinney doesn’t scare easy. Not after all the football playing and the lion taming and the parachute jumping and the one professional fight and the hundreds of unprofessional ones. But there was Jack McKinney sitting by himself in the middle of a street that was getting narrower all the time. He could see the Catholic mob on the left hand side stuffing the raggy torches in their bottled bombs. And the Protestants on the right pounding stones and bricks on their hands. The crowd started to creep in. For the first time in his life, Jack McKinney was really scared. Forty-one years flashed by. His own. He kept grinding at the ignition. A couple weeks before, another journalist had been killed in a similar uprising. That time it was by the troops. Grinding. These were his own people. Grinding. At least half of them were. Grinding, the crowd is almost on top of him now. Grinding, finally it starts. He throws it in gear and leaves some rubber behind as a calling card. That night, three other cars were stopped, at random, and their drivers were pulled out and pummeled as petrol bombs were thrown in and everything went up in flames and down in ashes.

MCKINNEY OBIT/HOLD IN OVERSET

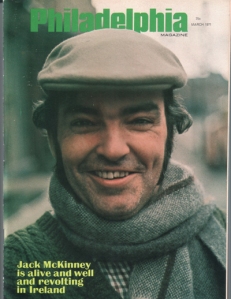

Jack McKinney was born at the age of seven on 3rd Street in Olney in North Philadelphia just a hop and a gallop away from the Saturday afternoon matinees at the Fern Rock theater. His parents were born in Ireland. He was the middle son of three. The first is a big shot chemical engineer. The third is a Texas millionaire.

McKinney, for all intents and purposes, did not go to college. He married Doris Cavanaugh, a singer. They had four boys and a girl. His first real job was with the Daily News as opera critic. He soon moved to the sports department, where he made a name for himself. The name was Jack McKinney. It won respect and awards.

McKinney fought one professional fight and turned down an offer to become general manager of the Philadelphia Eagles football team before leaving the newspaper business, in early 1965, to host a talk radio show on WCAU, the local CBS station.

The froggy-voiced McKinney was an instant success with his “Night Talk” program, gaining himself a national journalistic reputation playing Irish music and investigating the Kennedy assassination. “Night Talk” was the number one-rated show in Philadelphia until WCAU started screwing around with it. They stripped McKinney of his format, then his time slot, then his dignity.

McKinney started to dabble in other areas. He had a weekly television show on Channel 17 and a column in the Sunday Bulletin. Finally, in 1968, he gave up the radio show and started a nightly talk show on Channel 29. This is when he really died.

In August 1970, after investing good money in a hairpiece, he quit the television show and kissed his family goodbye and went off to Ireland to write a book about what had been commonly referred to by Irish people in the States as “The Trouble.” The Catholics in the six counties that make up British-aligned Ulster were rising in bloody conflict against the Protestant majority. They weren’t yet pressing for union with the Irish Free State to the south. They just wanted their civil rights.

McKinney had always been involved with the Irish plight, since 1949 when he led a demonstration against Sir Basil Brooke, “the little bastard.” McKinney was head of a group called “Friends of NICRA.” He sponsored rallies in Philadelphia for Bernadette Devlin, M.P., and other Northern Irish leaders. He was under secret investigation by the U.S. Government for running guns to subversive forces in Ireland, where he had many friends, including his cousin Manus, who is a technician for Aer Lingus in Dublin. McKinney was a rare Irish-American, one of the few men of his generation who stayed deeply involved with Ireland. His interest became an all-consuming passion, eating away at his very soul.

[HOLD FOR MORE DETAILS]

“OUR NATIONAL EPIC has yet to be written,” Dr. Sigerson says. John Cartin Alexis McKinney has come here to try. He has come here for many reasons:

—I made my decision to come over here almost overnight. My mind burst like a boil. I didn’t make it happen, it happened to me. It made me do what I did. I could make a strong case for myself being this incredibly brave, gallant type of person flying into the dark with dangers unknown and all that bullshit, but the fact of the matter is I wasn’t sailing into the dark. I knew that there was no way in the world that you could have the kind of national exposure I had for almost five years to a book-reading public and be flying into the dark about anything.

—I had said to myself as far back as last February. “As soon as I can, I’m going to phase out of the television business, and I’m going to sign with a publisher and I’m going to go over and write the book.” Then I procrastinated. I was trying to do something creative on television. You can’t quit in the middle. But I was constantly being nagged by the urge to do the book. And I suddenly realized that I wanted to be over here by the end of spring, certainly by June. And I wasn’t here and everything started happening. Bernadette went to jail, there was rioting, people were shot. I knew the next flashpoint would be the 12th of August, the day of the Apprentice Boys’ March in Derry. I knew that the civil rights movement was dying. What made it die? Was it sold out or did it just die of attrition or what? I just had to get over here.

—I went to the television station and told them I had an offer to write a book and it has to be done and I have to be over there now. And they agreed to let me out of my contract.

—On a Friday night I went off the air and on Monday night I was in a pub in Dublin talking to the former chief of staff of the IRA, discussing with him the possible ways and means to use myself as an influence to heal the rift in the IRA. My idea was that I would not go directly to the parties involved in the split, but to the people who were interested in a reconciliation, but—for one reason or another—were powerless to effect anything themselves. I came over here with the thought in mind that, as an outside agent, I might be able to effect a healing in the rift. Certain people wanted me to give it a try.

—The next day I rented a car to drive north. It was August 11th now, the day before the big march in Derry. I had to make good time but it was hard because things were tight. Two Ulster cops had just been blown to kingdom come by a booby-trapped abandoned car.

—It was a rough ride up. I was overwhelmed by the military presence. There was one stretch of road on my way up where I had to go for 36 miles on a no-pass road with a guy sitting in a military transport vehicle in front of me aiming a giant machine gun right at me. There were other soldiers with guns sitting all around him.

—It got me to thinking of the Russian invasion of Czechoslovakia and how much ink that got in the world press and how people were so outraged. And I saw what was going on in Northern Ireland—there it was right in front of me—and I was thinking about how completely neglected this story was back in the States. And I said to myself, “Goddammit, if I ever had any doubts that first night in Dublin when everyone told me what was going on, this has to expel them—just looking at these bastards crawling like red soldier ants all over the Irish soil, which they have no right to be on in the first place.”

—There was one military roadblock after another. There was one every 500 feet. I got sick of it. At every one they made you get out of the car and they searched everything. I decided not to play along. It’s just not in me. I decided to give them a little trouble. I made like I didn’t know anything about the country or its customs or its special vocabulary—like they call the trunk of the car the boot, and the hood the bonnet. I knew all that, but I came at them with this great wide-eyed innocent look of a middle-America tourist. They questioned me under the gun.

“Okay, what have you got in your boot?”

“My boot? Nothing, just my sock.”

“I’ll have you not getting smart with me, mister.” He walked around to the back of the car and pointed with his gun. “Come now, let’s have a look.”

“Oh, you mean the trunk. Why didn’t you say so?”

“Whatever the hell you call it, just open it up.” He searched and found nothing. “All right, now let’s have a peek under the bonnet.”

“The what?”

“The bonnet, man, the bonnet. And make it fast.”

“But I’m not wearing a hat.” I think he would have shot me right there if it wasn’t for my overly innocent face. Out of pure frustration he told me to get in the car and get the hell out of there. But I wasn’t quite finished with him. This time I opened my eyes even wider when I spoke.

“Can I ask you a question?”

“Yes, hurry, what is it?”

“Are you an Irish soldier?”

“Of course not. I’m British.”

“Then what are you doing in Ireland?” I don’t know what stopped him from putting a hole in me. I could see his trigger finger was getting nervous. Finally, to avoid temptation, I guess, he just slammed his gun down on the ground.

“It’s a long story, mister.”

—A long story. That’s for sure. That’s why I’ve been here six months now trying to piece the whole thing together. It took me the first few months just to get my bearings, just to figure out where the action was. Most people in the States think the whole damn war has been fought in Belfast. That’s far from the truth. It’s been fought all over Northern Ireland. It started in Derry. That’s where I was going when the soldier stopped me. Up till then, I’d been traveling in the Free State—the 26 counties of the Republic of Ireland. Derry, like Belfast, is part of the six counties of Ulster, technically part of the British Isles. But then, that’s what this whole mess is

about. It’s not the sectarian fight most people think it is. This isn’t a religious war. The fight is between the Unionists, those who seek alignment with England, and the non-Unionists —the people who think that the six counties should be part of Britain and those who think they should be part of Free Ireland. The only way religion gets involved here is through classes. This is a class struggle. The Ulster upper class owns just about all the land and all the industry. Most of them are long-line descendants from some sort of British royalty. All of them are Protestants. The working class is a different story. The working class has a phenomenal history of being repressed. And the bottom of the working class in the six counties of the North is Catholic. The Catholics are the niggers of the North.

—Anyway, when I got up there Derry was sealed so tight there was no chance of getting in or out. I picked up a newspaper and saw what was to become a stereotyped headline:

“DERRY SURROUNDED BY RING OF STEEL.” There were five thousand troops there and loads of extra police. I got in through a back road, with the help of a former IRA man.

—The Apprentice Boys’ March there is a yearly thing. It’s a flaunting of class by the Protestants. It’s an insult to the Catholics. This time it had to mean trouble, and it did. The troops were ready. All the riot prevention gear was out. When the Catholics came out, they used the water cannon to shoot a slick oil all over the street so the people couldn’t run away. Then they started shooting rubber bullets. The idea behind the rubber bullets is to shoot them into the street at the foot of the mob and have them ricochet off and knock people cold. Supposedly they couldn’t kill you, just knock your eyes out. Then they came in with CS gas. That’s a nausea gas that’s ten times worse than tear gas. It’s got a fantastic staying power. After all this, they brought the snatch squads in. It was the first time I saw them in action, but it was far from the last. They got to be a common thing, these Martian-looking troops all decked out in steel suits with shields and helmeted masks. They marched down the streets in a V formation from sidewalk to sidewalk, all the time swinging these four-or-five-foot-long batons at anyone who didn’t have the strength to run. Then they’d snatch them up and cart them off to jail. It was a really frightening thing, especially because I knew some of the people involved.

—I spoke to my contacts in Derry and from there on started to wander all over the North. I was just probing to find out what was going to be the most sensitive area. Where would I get the best for my time invested? I spent a few days in Belfast and kept moving around. Inevitably the answer was Belfast. I saw nothing was going to happen in Derry. The people there were bone weary. They had given up on themselves. The people in Belfast traditionally have a much tougher nature, probably because it’s more a minority situation here and they’ve lived a defensive existence all of their lives. So they’re conditioned from the time they’re born to defend themselves—to fight for their lives.

—I never intended to take up any sort of a permanent residence here. But by the middle of September, I could see that the job of covering everything I wanted to cover was going to take longer than I expected. Up until then I was staying with relatives and friends. One of those friends told me of a flat that was about to become available and I grabbed it. It just so happened that Bernadette Devlin had a place just down the street. But I didn’t see much of her in those first months. She was spending her time in Armagh woman’s prison, serving a six-month sentence for her part in the 1969 riots in Derry.

WHEN THE PEOPLE in Belfast all die and go to hell, it will be a definite improvement in their living conditions. Belfast is the Marcus Hook of Ulster. The people know it. They don’t exactly encourage the tourist trade. Most of that is kept in the South, a place of beauty reached daily by the sleek silver birds of Aer Lingus, one of the world’s most amiable airlines. “Have a sweet,” says the pretty stewardess. “Hope you’ll fly down South after you investigate ‘The Trouble.’ ” It is no coincidence that Aer Lingus (Irish International to you) only flies from Dublin to Belfast twice a week. You fly in to Dublin from America over the South, a gently smooth 707 ride over this fantastically beautiful green patchwork quilt. An emerald set in the ring of the sea. Then you change planes to fly north. The clouds greet you at the border. They get darker and dirtier as you approach Belfast. There is no color in Belfast. There isn’t even any black and white. Everything is gray. All of the pictures that go with this story were shot with color film. Look at them. They were all taken between 2:10 and 2:15 in the afternoon. That is when it does not rain. The Belfast skyline is three stories high. You look around and there probably hasn’t been a new building put up in the past 50 years, maybe 100. If the 19th century ever comes back, this town is going to thrive.

McKinney’s flat is in one of the better sections of Belfast. He has four rooms, including the water closet. None of them are connected, none of them are heated. A portable radiator and a coal-burning fireplace help take the frostbite out of the main room, which serves as bedroom, dining room, living room and work area.

Under all the dirty clothes and folded newspapers are a sofa and a couple of chairs. It is hardly worth the moving job to sit down. The flat, like the man, is sloppy and disorganized, just as expected. It is the nature of the man. Jack McKinney does not belch in public for nothing you know.

McKinney is living a second childhood over here. If he doesn’t know it, everyone who knows him does. “It’s the only thing that makes his being gone so long explainable,” says Doris McKinney from Ardmore. “He’s wanted to do this as long as I’ve known him. I guess every man’s entitled to play the lead in his own dream.

For financial reasons, McKinney’s dream did not include his family. He hasn’t seen them since August. Part of the problem is that he’s over here on his own money, mostly borrowed. It might have been a lot easier to work with a big, fat advance from a publisher, but McKinney didn’t want to spend the extra time in the States bickering over bread. He wanted to get over as fast as he could on his own terms. The assurance that he had three major publishers interested enough to be waving money in their fists was enough to convince him that the bargaining could be done when he wanted and on his terms. That’s the way McKinney works.

So he is living from day to day with only the barest necessities. The only rug in the place is on his head. He’s let his own hair grow longer. It’s curling over his ears now and down the back of his neck. He had a full beard at one time. Then he shaved off the chin growth and left himself with a great Viva Zapata moustache. But the locals, conservative lot that they are, found it a bit much. So McKinney, already aware of being overly conspicuous, took it all off, now just moving around in his usual corduroys, beat up boots and well worn Irish sweater.

The only reason he grew anything in the first place was to give himself something to do. The pubs close at 10 p.m. on weeknights, midnight on the weekend. Unless there’s a good riot going, there isn’t much to do in Belfast but go back to your room and read the papers or transcribe interview tapes.

Much of McKinney’s work here has been tedious, interviewing people for hours hoping to get just a line or two of clear insight or a good quote. He’s been at the mercy of everybody else’s time schedule. That often means skipping meals and sleep. It doesn’t matter much. McKinney has to do a lot of his own cooking. Most of the time, not eating is healthier. And the most you could say for the finest restaurants in Belfast is that their food is tolerable. Irish cooking is not the world’s greatest. In fact, when he does eat out, McKinney tends to favor places like the Chinese restaurant a few blocks away.

The people he eats and drinks with are usually all of the same persuasion —religiously, if not politically. He makes no bones about his book being a minority report. Admittedly, he came over to write it from one point of view.

—I believe in advocacy journalism. I don’t believe that anyone is objective in journalism. I think that anybody who claims to be is being hypocritical and downright fraudulent. My point of view is too well known to try to do anything objectively.

—My interest, though, isn’t sectarian. I don’t think of myself as an Irish Catholic. I think of myself as an Irish socialist, which might be a naughty word in the States. But I believe the only way that the 800 years of systematic plundering in Ireland can be redressed, the only way that there can ever be stability here, in equity, is that there has to be a revolution.

—The revolution can start here or it can start in the 26 counties. It’s immaterial. But the fact of the matter is that it has to touch and affect all of the 32 counties. And that revolution has to be a socialist revolution. And with it we’ll have the apparatus for the expropriation of the major industries, and redistribution of the wealth of the land to the people. So little of this land, both in the North and in the South, is owned by the people. It’s owned by absentee landlords, by foreign investors.

—It doesn’t necessarily have to be an armed revolution if a social revolution can accomplish it. Right now, the people I favor are the ones who would be considered the moderates when it comes to the use of armed force. The Official IRA has put armed force in a less prominent priority. Armed force, as far as they’re concerned, is probably inevitable. But there are two different types of armed force—the armed force of defense, which they feel should get a high priority, and the armed force of pre-emptive initiative, which they feel should get a very low priority.

—The Official IRA, what’s commonly called the Dublin wing, call themselves the National Liberation Front. There’s tremendous sympathy for the Viet Cong here. Despite the fact that Ireland has traditionally been a friend of the United States because of the tremendous migration and so forth, the majority of the Irish Catholic people relate to the Viet Cong. They think what the United States is doing in Vietnam is nothing short of a war crime.

Our Jack McKinney—a Marxist? He has a poster of Karl Marx hanging over his bed, right near the one of Martin Luther King, and right across from one of the other Marx brothers.

—I thought of putting those two posters side by side—you know, Groucho, Chico, Harpo and Pinko.

You have to consider the time and the place and the mood before you consider McKinney’s posters reflective of his politics. You also have to consider that the wallpaper in his room is terrible and posters are about the cheapest way of covering things up. There is no particular logic behind any of it—Tom Paxton hanging next to Che Guevera. The room looks like it belongs to a college sophomore. And, in one sense, maybe it does. But politically, McKinney is a little bit past the wall-reading stage. He’s also got an obligation to his role as peacemaker within the movement to try to relate to as many different factions of it as he can.

The thing that has been screwing up the whole revolution is what McKinney, not to mention Freud, calls the hostility of small difference. What it amounts to is a total fragmentation of forces whose aim is the same. The only difference is how to achieve it.

The Irish Republican Army, the force that won Ireland’s partial independence in 1921, has long been both outlawed and active. But the IRA has splintered into so many factions, you need a scorecard. The Official IRA has disowned the more militant Provisional IRA, the group perhaps most responsible for initiating terrorism. And the Provisionals have, in turn, disowned the Officials. The Sinn Fein, the political arm of the IRA, is also split. And around the major split are a million little splinters—the Marxists, the Communists, the Socialists, the Liberals, the list goes on. They all want to unite Ulster with the South, but they are all opposed to each other’s tactics. While they are fighting among themselves, they are getting slaughtered in the common battle.

Jack McKinney’s role in this thing is almost unbelievable. He has become perhaps the only man in Ireland who can easily and openly talk with the leaders of every faction. In less than six months, Jack McKinney has become the hero of his own book. He is no longer an author in search of a story. He has become the story, in search of an ending. And the search has taken him everywhere.

TENSION. You can smell it in the Derry air. McKinney has driven up from Belfast. Four hours behind sputtering trucks and grazing herds of cattle. In Ireland, the cattle have the right of way. His first meeting is set for half-noon. It’s already past that and there’s an hour ahead at least. McKinney has fallen into the life style. Never do today what you can put off until tomorrow. Time doesn’t mean anything in Ireland. There is no such thing as being late. People say things like, “I’ll see you next week,” when they want to be precise. It is a quiet land. That’s the irony of the revolution. It’s a lazy land of people with nowhere to go in a hurry. Maybe it is better to live like that. There are few ulcers in Ulster.

Derry is right near the border. McKinney has relatives on the other side, in the Free State. He decides to visit them, taking an outlaw road across to avoid customs. You can get arrested for that kind of stuff. Of course, the worst they could do to McKinney is deport him. And don’t think they haven’t thought of it.

In Derry, the walled city (Protestants inside, Catholics out) , he talks with Brigit Bond, leader of the Derry Housing Committee. They go over the background of the early civil rights demonstrations—how it all started with Catholics squatting over inequitable housing. Brigit Bond goes on for hours.

It is dark by the time McKinney gets to Eamonn Melaugh’s. Melaugh is one of the more militant leaders in Derry. He’s got enough to be mad about. He’s got a wife and nine kids and no job. That’s one of the things that touches you about the whole movement—people like Melaugh with nine kids, Frank Gogarty with six, taking to the streets and putting their lives on the line for what they believe in. They’ve got to be either sincere or crazy.

Melaugh gives McKinney some good first-hand riot experience. He tells him how he was beaten when he tried to come to the aid of a fallen pregnant woman who was being beaten and kicked in the stomach by cops and soldiers. He tells McKinney something has got to happen soon. He expects it to come from the Provisional wing of the IRA. “Those people have worked themselves up to such a fever pitch, there’ll be no stopping them. If they’re not provoked soon, they’ll do the provoking. You can’t keep them down long. It’s like taking a fine thoroughbred horse and getting him in the best possible racing condition and then locking him up in his stall. Well, hell, man, he’s going to kick the damn stall down.”

Melaugh is a prophet. That night the BBC transmitter near Belfast is bombed, and two nights later, the whole stall is kicked down.

Before the long ride back to Belfast, McKinney stops off to see Eamonn McCann, who lives with his father in the Bogside, the Catholic ghetto of Derry where it all started. McCann wants to leave the house because he has just had an argument with his father. There is something to be said against a revolution whose most brilliant leader isn’t even the master of his own house.

They drive down to the Bogside Inn, where they meet an old IRA man and share some Guinness stout and some old stories. His tank full, McKinney drives back to Belfast to catch a few hours sleep before another day at the typewriter. The presence of armed troops around Belfast is heavier than ever that night. Something is up.

THE NEXT DAY, Cathal Goulding, chief of staff of the Official IRA, comes knocking at McKinney’s door. Later that night, McCann returns with Queen Bernadette, who has become little more than a memorial figurehead to the cadaver of the civil rights movement. “She still has deep convictions,” McKinney says, “but she’s become a doctrinaire socialist who really doesn’t understand all the nuances and intricacies of socialism. She’s just not practical any more.”

Practical or not, the wee girl is still considered a leader and still followed wherever she goes. So is Jack McKinney. But in his case, it’s a different kind of follower. He is under close surveillance here. The authorities make little effort to hide it. The Ulster Special Branch police and the military are stationed outside his flat on most occasions. They’re always making passes by in their official cars. When he leaves, they follow him.

His phone is tapped. They’ve even been crude enough to come on the line on at least three separate occasions. He had heard clicking since the day the phone was installed. But one clay his suspicions came true when he hung up from one call and quickly picked up the receiver to make another and heard a voice say, “You can shut it off now, they’re finished.” Another time he was talking to a friend in Dublin when the clicking started. “Sounds like you’ve got visitors, Jack,” the friend said. “It could be on your end,” McKinney said. “You know they do that in Dublin, too.” Enter the third voice: “What was that you said about Dublin?”

The third time, the interruption was in the form of a warning. McKinney was talking politics and went and called the Ulster government a dirty something or other. “You’d better watch that stuff,” the third voice said.

The tap doesn’t stop with the phone. They also open all his mail. At first, they tried to be a little professional about it. They would steam the letters open and paste them closed. Only the damp curling effect of the iron gave it away. Now they don’t even bother with such courtesies. The envelopes come ripped open any old place, closed up again with tape. It’s the price you pay for leadership. It’s the price you pay when you come over to cover news and end up being news yourself. There are two Jack McKinneys in Ireland. There is Jack McKinney the journalist and Jack McKinney the revolutionary. In times of trouble, the two are inseparable.

THERE HAS BEEN RIOTING every night in the Ballymurphy area. Each night it gets worse. Sectarian mobs confront each other on the Springfield Road, the Protestants and the Catholics badlooking each other. Two buses have been hijacked and driven into houses at high speed, causing considerable damage. Three British Land Rovers have been attacked with petrol bombs. The British troops are under nightly attack. There have been arrests every night.

Meanwhile, Ardoyne, another battled and burned Belfast neighborhood, is heating up because of the trial of the Ardoyne Five—five men who were being held in prison on charges including “conspiring to murder person or persons unknown.” These men, Catholics, were fingered by their not-so-friendly Protestant neighbors across the Crumlin Road, which serves as Ardoyne’s narrow DMZ. They were held for weeks without bail, without charge.

Frank Gogarty was setting up most of the protest rallies in Ardoyne, but he was having trouble getting speakers because too many people were afraid of being thrown in jail for opening their mouths. Jack McKinney had covered many of those rallies. But now Frank Gogarty was asking him to do something different. He was asking him to be a speaker. McKinney said he’d rather not, but if the success of the rally depended on it, then he would.

A Socialist spoke, a Communist spoke, a housewife spoke. The crowd of more than 500 was getting uneasy, blowing with the winds of a popsicle night. Jack McKinney was introduced as a distinguished friend of the civil rights movement in the North of Ireland. He got up on the flatbed truck and looked out over the waiting crowd. There were British troops all around, their guns at the ready, listening to and taping every word that was said, waiting for the slightest provocation. McKinney pulled his cap down a notch tighter over his quickly graying black hair.

“You’ve heard a lot of platitudes tonight,” he growled. “I’m not going to stand up here and lecture you on the British powers of arrest because too many of your breadwinners, too many of your sons are already suffering from them in the Crumlin Road prison. I’m not going to lecture you on political ideology. I think the people of the North have been bombarded by a lot of things, and one of them is rhetoric. I’m not going to give you a lot of tub-thumping rhetoric. Instead I’m going to give you something that has a little substance to it.

“I was speaking to Frank Gogarty before and he told me how frustrated he was because all he could give you was words. Well, I’m going to give you more than words. I’m going to give you witness. I’m going to tell your story to the world. And I’m going to let the world know about this unbelievable Orwellian environment. I’m going to look behind every bush. I’m going to leave nothing unturned that I can turn to show the criminal miscarriage that is taking place in the case of these men in Ardoyne.”

The crowd was on fire now as McKinney told them of a meeting between Jack Lynch, prime minister of the Free State, and Ted Heath, prime minister of England, where Lynch told Heath that he was satisfied with the rate of progress toward reform in Ulster. McKinney began pounding his fist in his hand.

“Well, what is satisfactory for Jack Lynch in the Free State is not satisfactory for Ardoyne. If Jack Lynch is satisfied that you are arriving at an equitable living condition, then I say let Jack Lynch spend a week on the Crumlin Road. Or let Jack Lynch spend a week in Ardoyne.”

The crowd was wild with cheers. Jack McKinney stepped down off the flatbed truck and they swept him to the front. He locked arms with the leaders and the rest followed, marching through the streets of Ardoyne, over the curbstones of a battled Belfast, singing the songs of the revolution.

They marched to the beat of the bombs that fired off in the distance. Their path was lighted by the fires of revolution that singed the sky. Some of their faces were hard and beaten, some of them were afraid. Only the man in the front with his cap pulled down showed a smile. Jack McKinney had come home.

Some genuinely superb posts on this web site, regards for contribution.