How the Phillies’ all-time home run hero ended up being king of the hoagies.

By Maury Z. Levy

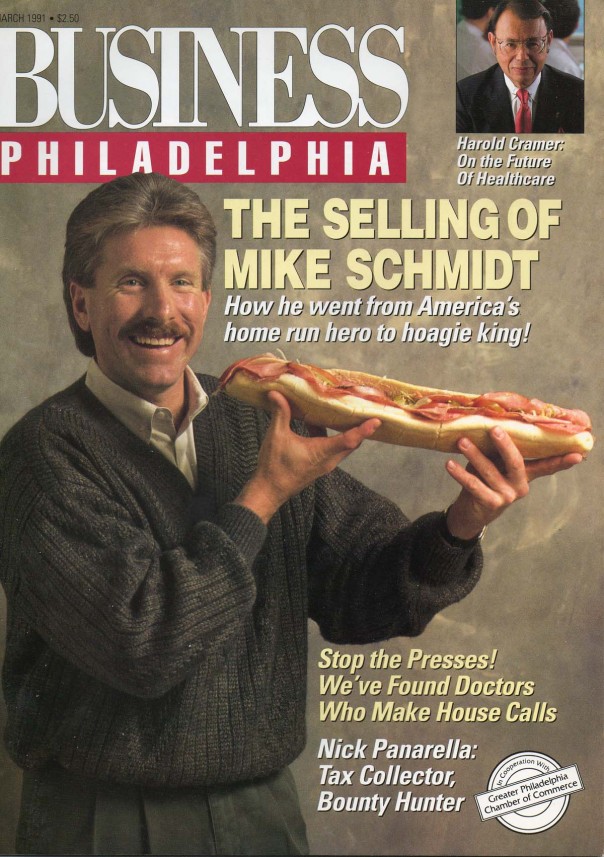

THE CHEERING HAS BEEN OVER FOR OVER A YEAR now. And the booing, that callous cacophony that alternately drove him to his best and drove him to the brink, is but a bitter memory. Now, out here in the real world where fair trade weighs heavier than foul balls, it is time for Mike Schmidt to wake up and smell the onions. Mike Schmidt, one of the best baseball players who ever lived, one of the greatest natural athletes in the history of sport, has had old number 20 retired, thank you very much, and is now selling hoagies in Richboro.

There is something about that that makes Mike Schmidt proud and something that makes him angry. Bo Jackson, who sells Nikes out the wazoo, will never hit as many home runs as Mike Schmidt, but he’s on television every three minutes. Geez, even Tim McCarver, a nice guy but an average baseball player, beat Mike Schmidt out for a job as a color analyst on network TV. Tim McCarver couldn’t hold Schmidt’s bat when they played together in that championship season, but Tim McCarver, who does shtick, who tells bad jokes, who makes corny puns, is at network now.

And Lenny Dykstra, who’s had a good year or two as a baseball player, but is a pig of a man, will make more than Mike Schmidt ever made. And he will show up on David Letterman. And he will, like former felon Pete Rose, have kids across America sliding head first and getting dirty and learning how to spit and curse and dribble down their shirts.

But what about Mike Schmidt? What about the man with all the Gold Gloves? What about the man who hit more home runs than almost anyone else on the planet? What about everybody’s All-American? Tomorrow, he will be in the Hall of Fame. Today, he is selling hoagies in Richboro. He just doesn’t understand it. Then again, maybe he does.

“I DON’T LIKE COMPARISONS,” SCHMIDT SAYS. ”But I would think that my career speaks for itself. My image speaks for itself. My track record speaks for itself. My honesty, integrity, family life, all the things I’ve ever stood for and accomplished in my career are marketable.

“Occasionally, I get a little jealous that I’m not as easily marketable as an Andre Agassi, because he’s not married, he wears that off-the-wall shit, and he can do whatever he wants. There are a lot of people who can get away with doing things that make me a little jealous, things that I never did or can’t do now to help market myself.

“I’m marketable to Dean Witter and to banks and things like that. I’m marketable for the honest family man in me. And I have the local milk commercials and the Chevy spots. But I’m not a rebel. I’m not a guy who came back from drug addiction. I’m not a guy that people are lined up to write a book about because I spent two years in prison.

“I have a lot of fun in my own little circle. I wouldn’t want things to be any different. But you have to wonder about marketability. Maybe if I played the game like Dykstra plays it, maybe right now I’d have a toothpaste commercial, I’d be spokesman for Pepsodent or something if I grossed out the whole world with tobacco falling out of my mouth and down my shirt for 18 years.

“Maybe now somebody would hire me as a spokesman. If you’re a rebel, if you do crazy things, you’re more marketable.

“I could have had much less of a career if there had been more trouble, if I’d been traded more, gone to other towns. I could have been a lot less of a player and maybe snuck into a World Series with this team and gotten into one with that team. You know, been a very mediocre player but always seemed to pop up at the right time and get a big hit in October. That kind of guy is probably a lot more marketable than me—a guy who played 18 years in the same city and is going to the Hall of Fame.”

But Mike Schmidt stayed. He didn’t do drugs, he didn’t gamble, he didn’t even spit. And what’s it gotten him? A sure spot in the Hall of Fame. And hoagies in Richboro.

AT FIRST,” HE SAYS, “I DIDN’T Like the whole idea. I get a whole hack of a lot of calls for me to do deals with people. Believe me, they are not the kind of calls Donald Trump is getting. They are people with their own little businesses, and they’re not billion dollar offers. In fact, there are very few six figure offers. People want to try to take advantage of my name in the Philadelphia area much more so than nationally. It’s small stuff. I’m inundated with that.

“My wife is a lot more wary about things than I am. Every time I get a call from my agent, Arthur Rosenberg, Donna says, ‘He’s not calling with another one of those submarine deals, is he?’ Seems we got into a deal with a submarine project that didn’t get off the ground. She won’t let me forget that one. So when the call came in about the hoagie deal, Donna was kind of cautious. ‘Hoagies,’ she said. ‘Now we got people with hoagie shops wanting you to get involved? You’ve got to be kidding!”

Schmidt is already in a restaurant deal in Center City. Michael Jack’s, the sports bar and eaterie on Market Street. It’s been quite successful. So why, as Donna Schmidt would ask, another food place?

“I guess she had a point,” Schmidt says, “I know the look and feel of your average neighborhood carry-out hoagie shop. Why would I want to put my name on the outside of one of those places?

“I’m very particular about what I lend my name to. I was the same way with bats in baseball. I had a contract with Adirondack bats. They gave me the best service they might have ever given a baseball player. In fact, I might be the only exclusive Adirondack user in the 500 home run club. And even if I ever did love to use a Louisville Slugger bat, I’d at least tape a red ring on it so it looked like an Adirondack.

“In fact, loyalty to the product got me in real trouble once. Nike hired me to help introduce their new line of baseball shoes. But they hadn’t really developed a shoe that fit me well enough to wear on the field yet. I was so excited having money paid to me by a shoe comp any that I wanted to really get to work for them. So I took an old pair of Mizuno shoes that I loved and cut the swoosh logos off a pair of Nikes and pasted them right on the Mizunos. And somebody in the clubhouse blew the whistle on me. For what? For trying to be loyal to a deal. So I cut the damn logo off one of the Nikes and put it on a shoe that fit me. So? So there was a law suit and a big stink.”

HAT TURNED SCHMIDT AROUND on the hoagie deal? He finally met with Mike and Rich Speeney, the guys from Richboro, listened to their philosophy and saw their projected numbers.

“This thing could be national,” he says of the two-store chain now called Mike Schmidt’s Philadelphia Hoagies. “I could really help promote it in my travels. The shops have the environment I would love to take my kids to. Big booths, a nice sports gallery. You don’t generally want to stay in a place when you order a hoagie or a cheesesteak. You want to just bag it and take it home. But this place you want to just stay for a while. It’s so clean.”

HE IS A CLEAN FREAK, MIKE SCHMIDT. WHEN we showed up at his business office in Malvern, he was down on his knees wiping the dust off the end table next to the sofa across from the desk in front of the giant photo of the 1980 World Series celebration, where Schmidt, showing as much emotion as he’s ever shown on a baseball field, is jumping all over reliever Tug McGraw.

It is clearly the office of a former baseball player. The carpet is blue-green, a whiter shade of Astroturf. There is a crystal baseball on the desk, a porcelain miniature of Schmitty at the bat on the table. He shares the Lancaster Avenue suite with a leasing company and some of his friends. Howard Eskin, roving sportscaster and prime collector of Schmidt memorabilia, is about to move in next door.

“We’ll have to save one of these hoagies for Howard,” Schmidt says, on a day when the Speeneys have brought him a bunch for an office tasting. “Just make sure you don’t get those onions on the floor.”

It’s this sort of cleanliness that made McDonald’s, Schmidt points out. “My God,” he says, “I’m not saying we’re going to catch up with McDonald’s, but eventually, probably within the next ten years, I’d like to see 100 of these stores around the country.”

MIKE SPEENEY, THE HOAGIE GUY, USED TO call his Richboro restaurant Richie D’s before he got the idea to hook his peppers to a star.

“We had a great product,” he says, “but it takes time to get a reputation. My sons and I decided we needed a celebrity to accelerate that process and help sell franchises. Mike Schmidt was the perfect choice. He’s a hero in the Delaware Valley.”

The Speeneys took the deal to Arthur Rosen‑ berg in Rydal, who put his expensive cowboy boots up on the desk and played hard to get. ”We receive three to four offers a week for Mike,” Rosenberg says. “Most of them are dismissed categorically because they’re not our kind of deal. Since Mike has retired, we’ve participated in only three or four, total. Mostly, they’ve been investment opportunities.”

Rosenberg eventually convinced Schmidt to make the almost two- hour drive from his home in Media to the Richboro shop, which was closer than the Doylestown shop. Schmidt was impressed with the operation. He was also impressed with the numbers.

“This is a great deal for him,” Mike Speeney says. “He doesn’t have to put any money in upfront, and he’s tied directly to the bottom line. Every time somebody buys a hoagie, every time the cash register rings, that’s money in Mike Schmidt’s pocket.”

Schmidt’s end? He gives his name, he shows up for some promotions, signs a few balls for customers and prospective franchisees, and he gets a mascot named after him. Once the costume is finished, Stogie Bear will become the Phillie Phanatic of Bucks County.

THE YEAR AND CHANGE out of baseball has been very good to Mike Schmidt. The sun and wind of all those golf tournaments have given him a perpetual tan. His hair is thick and full, his mustache as perfectly trimmed as ever. If he’s put on a pound or two, it’s hidden well under the bulky silk and wool sweater that serves as his business suit. Beneath it, you can still see the outline of a body that ripples, but doesn’t bulge. The ravages of his knees and quads and hamstrings aren’t visible as he walks. And his arms are still those magnificent pipes that would be at their powerful best at full extension—arms that would, for all those years, so effortlessly muscle a hardball past the point where mortal men would merely imagine.

He’s a businessman now, but he’s not terribly comfortable with it. “I don’t work 8 to 5, five days a week,” he says. “And I don’t work for anybody else. I’m trying to develop my own portfolio. My problem is my inability to network my ideas, to put them in motion. I haven’t gotten to that point yet where I’ve made the right associations, where if I have an idea for a project, whether it’s a golf tournament or a videotape, I could pass that idea down to a guy who will make it happen and report back to me. Some day, maybe, I will get to that point. Right now, I’m taking a couple of years out of my life and trying to decide if I have that kind of savvy. I may not. I hope that I do, but I may end up in a baseball uniform as a batting coach or manager a few years from now when my kids are grown up. And maybe that’s where I belong.”

THE QUESTION THAT burns, and eats away at him some days, is why is this living legend still peeling small potatoes. Is it Philadelphia? Would the big offers be rolling in had he played in New York or L.A.? That’s a pretty hard argument to make as long as Julius Erving’s in Philly. But Schmidt sees one very big difference between his marketability and the Doc’s.

It’s kind of a scary revelation when you see it in his eyes. Mike Schmidt has come to the definite conclusion that, for pure market value, he played all those years in the wrong sport.

“I played a sport where one guy never made that much difference on a team,” he says. “It took me 18 years to develop an awareness of myself as an athlete where people would compare me to the all-time greets. It took Julius about a week in the NBA. To be one of the all-time greats, it took me years of surviving in the sport and amassing numbers to compare with other people. And all of a sudden, there it is. Goddamn, this guy Schmidt might be one of the ten best players to ever play the game.

“My sport didn’t give me instant fame, not like some basketball players and golfers and tennis players. Baseball is a dirty sport. There isn’t a lot we can do to create the novelty and excitement of a slam dunk. Turn on the TV tonight and count the number of commercials you have with basketball players slam-dunking. There’s got to be at least 15 of them.

“In football, there’s the touchdown dance. In tennis, there’s the Agassi approach. What does baseball have but longevity? Look, no one’s ever hit more home runs in a game than I have. But it took me two-and-a-half hours to do it. And it didn’t get exciting until after the third home run.

MAYBE BASEBALL IS more of a religion than a sport,” Schmidt says. You believe in it for a long time, and it’s always there. You get taken for granted when you play the game. The difference is not many of us have dunked a basketball, so that’s something magic. But all of us have hit a home run somewhere in our lives. We’ve all circled the bases. We’ve all had a ground ball hit to us and had it go through our legs. And that makes just about everybody say, ‘If I wanted to play baseball, I could have.’

“So there’s not that much of an appreciation for me hitting a home run. I had to hit almost 500 of them before people started to appreciate it. But they appreciate that first slam dunk by Charles Barkley because it’s something they could only dream about doing. Hey, even I look forward to those dreams where I dunk a basketball.

“I’ve had to work harder at success, when I was playing and now that I’m through. And I have to work hard now to cash in on it. I don’t like going around telling people Mike Schmidt was a great baseball player. I don’t like that at all. It’s not my nature. But if it helps to close a business deal, then I’ve got to do it.

“You know,” his hand is a fist now, “it just shouldn’t be this hard. My career speaks for itself. And my image speaks for itself. I just don’t understand it sometimes.”

He looks down at a copy of Business Philadelphia sitting on his desk. There is a picture of Tastykake CEO Nelson Harris on the cover.

“Hey, I know this guy,” Schmidt says. “I see him at functions around the city. How come he doesn’t call me? What would be a more perfect image for Tastemaker? I’m already doing the milk commercials. This would be a natural. A legend with a legendary product. So how come this guy doesn’t call me?”

It is lunch time now. Mike Schmidt takes a big bite of a hoagie and waits by the phone.

MIKE SCHMIDT: SECRETS OF SUCCESS

Things came easy for me,” Schmidt says. “People were generally jealous of me. I was a great player because things didn’t look hard for me. Things looked easy for me. So people never thought I was giving 100 percent because I didn’t need to.

“I didn’t have to dive for the ball because I could just catch it like that and throw the guy out. Players like Rose and Dykstra, everything looks hard. People relate to them more than they relate to me. Things are hard for the normal man. Hitting a home run. A lot of emotion and a lot of effort goes into people succeeding. Normal people looked at me like I was the kind of guy that didn’t need that kind of hard work and emotion to succeed. So there was an animosity toward me throughout my whole career in this city.

“But that’s just life. I don’t want to do it over. Besides, I think there’s a great deal of respect for me in this town now.”